The Cultural Foundations of the Fountain and Lithia Park

People make parks.

Article by Pat Acklin, Fountain Restoration Steering Committee Member

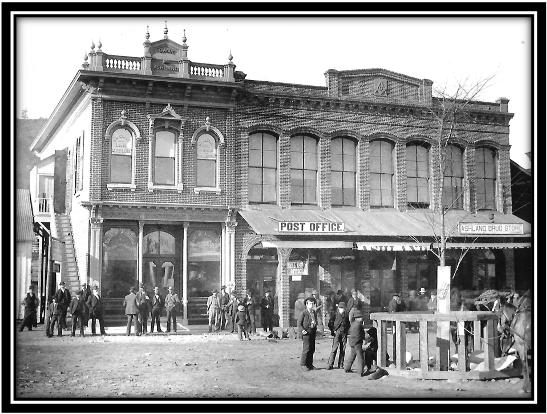

Ashland is fortunate that its 19th and early 20th century residents were people of such foresight. These citizens kept up with the progressive ideas of their time and implemented them here. Many aspects of the town today, e.g., Lithia Park and the Butler-Perozzi fountain, reflect not only their values, but values around townsite consciousness and the natural landscape as an aesthetic and cultural resource that were being embraced at the time.

Frederick Law Olmsted, who with Calvert Vaux designed and built Central Park (1853), is recognized as the pioneer landscape architect of this time. Olmsted, along with architect Daniel Burnham, designed the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition or World’s Fair. Together they created a model city that captivated the imagination of architects, city planners, and citizens and brought the world the first potable drinking water fountains, AC electricity, and the Ferris Wheel. Olmsted assisted with selection of the location and converted swamp into lagoons and a wooded island to be enjoyed from the water. He intended his natural landscape to combat the bustling atmosphere of the fair, providing a place of calm and serenity. Many believe that this Exposition with its blend of city planning, public art, and landscape parks was the beginning of the City Beautiful movement, a movement we can see on the ground right here in Ashland.

There were a couple of other things going on in the country that influenced Ashland in the late 19th century. One of these was the growth of Improvement Associations in small and medium cities around the nation, beginning in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey. Activities included upgrades of commons, streets, gravel sidewalks, and tree planting. “Cleanliness, order, and cultural activity as well as picturesque landscape amenities” were part of the ideal. Women dominated these groups. Ashland had its very own Women’s Civic Improvement Club.

The group forced the issue of a park at the abandoned Ashland Flouring Mills and the “pig sty, cow barns, dilapidated old fences and mud puddles behind.” An election was held December 17, 1908 to create Lithia Park. The group was also responsible for Triangle Park, a park on Gresham & Main which later became the Carnegie Library grounds, the Median on Siskiyou Boulevard, and the encouragement of residential landscapes

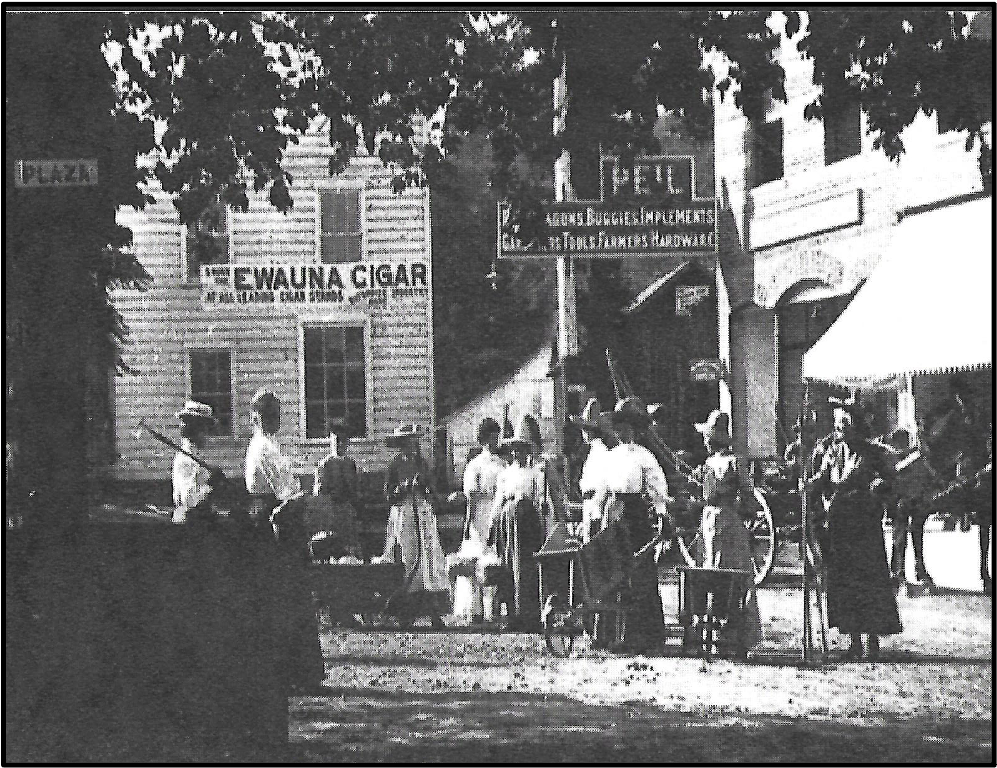

Another national movement present in Ashland was Chautauqua which brought entertainment and culture for the whole community, with speakers, teachers, musicians, showmen, preachers, and specialists of the day. It came to in Ashland in 1893. In 1899 Charles Mulford Robinson presented the idea of City Beautiful to the Chautauqua Association. The Chautauqua Association embraced these ideas and those of the Civic Improvement Association and distributed them widely, sending literature to its chapters across the country, including Ashland.Three principles were embraced by local communities – sanitation and paved streets, parks mixed in the street grid, and public art.

Here’s how it played out in Ashland:

1908 – Park election, Park Commission formed, mill torn down

1909 – Sewage treatment in the form of a large septic tank

1910 – Streets paved; sidewalks built

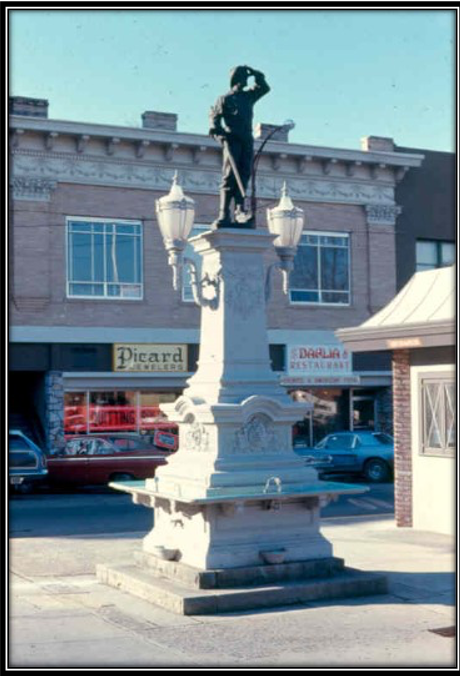

1912 – Plaza adorned by the first public art, a pioneer statue

on the plaza donated by the Carter family

1915 – Park expanded; Butler – Perozzi Fountain added

1922 – Statue placed at the Carnegie Library

The City Beautiful movement has been criticized by some because its manifestation in large cities and elsewhere often resulted in monumental buildings of neoclassical architecture. Professor Rutherford H. Platt notes, “From Washington D.C. to Cleveland, Denver to Seattle, the nation’s older city centers are still dominated by public spaces and pompous architecture from the City Beautiful era.” However, in Ashland and in dozens of towns and small cities across the country, the improvements made during this time period add character, beauty, and charm that continues to contribute to the livability of these places.